In the early medieval period, the principal location in Northumberland was the coastal town of Bamburgh. In fact, from the time of the Celtic Britons this region was home to some form of early fortification. The current incarnation of Bamburgh Castle is built on a northeast facing outcrop of the Great whin Sill, an intrusion of volcanic rock covering around 4,000km2 of northern England. Sitting 45m above the sea, the castle towers over the present village and offers an excellent defensive outlook to the sea and the inner islands. It is unsurprising then that with each new dynasty this location would be occupied by an ever-evolving fortification.

The Angles arrive

In 540 AD, Gildas a British monk penned an emotional account of the arrival of the Saxons from Germany, Frisia and Denmark a century before. In his De Excidio et Conquestu Britanniae (On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain) Gildas accused the ruling Britons of having brought upon themselves ‘the fierce and impious Saxons, a race hateful to both God and men’ in their attempts to battle the northern tribes. These incomers expanded north and west across Britain creating new kingdoms as they went. One Anglian king in particular, Ida, set his sights on Bamburgh and conquered the Celtic kingdom of Bryneich. The sources are few but one of the most well respected was Bede who was writing in the first half of the eighth century and he tells us that ‘in the 547, Ida began to reign’. The Anglo-Saxon chronicle then elaborates that ‘He reigned for twelve years, and built Bamburgh, which was at first enclosed by a stockade, then a wall’. From here, Ida made use of the strategic location of the old Celtic fort to rule the kingdom of Bernicia.

The fortification

The first Anglo-Saxon fortification at Bamburgh would have consisted of timber defences and buildings just one storey high, a stark contrast to the stone castle we see today but no less effective in 6th century Northumbria. These same wooden palisades, according to Bede, came under attack by Penda, king of the Mercians. In 651 AD, Penda attempted to set the defences alight. However, Aidan the monk turned bishop whom King Oswald brought from Iona, saw the flames from Lindisfarne Priory. Aidan is said to have prayed for Penda’s defeat, after which the wind changed direction and blew the fire and its thick black smoke back at the Mercians.

Archaeologically, the Anglo-Saxon structures at Bamburgh have provided some key insights into their way of life. The Bamburgh Research Project were able to unearth skeletal remains of an Anglo-Saxon male from which a facial reconstruction could be obtained. Furthermore, excavations and supplementary written evidence give us some idea of the layout of the buildings at Bamburgh. Research suggests that there would have been a large timber hall surrounded by several smaller inner structures. This type of king’s hall is not unlike the one described in the epic poem, Beowulf. The descriptions of the Hall of Heorot provide potential further reading for those interested, after all some historians have argued that the poem was written by a 7th or 8th century Northumbrian poet, perhaps even at Bamburgh?

Great Kingdoms and Godly Men

(Stain Glass Depiction of Saint King Edwin –

Thomas Gun https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Saint_King_Edwin_of_Northumbria.jpg)

Bamburgh being the principal seat of power meant that it often provided the backdrop for some of the most significant events in Northumbrian Anglo-Saxon history. In particular, the careers and deed of Northumbria’s saint-kings.

Neighbour to Bernicia was the kingdom of Deira. In 589 AD an infant by the name of Edwin was the heir to the throne of Deira when his father died. Due to the boys age his uncle Ethelric dispossessed him and became king. When Ethelric himself died in 604 AD his son Æthelfrith, who had been ruling Bernicia, ascended the throne of Deira thus uniting the two kingdoms into one Northumbrian domain.

It was this King Ethelfrith who gave Bamburgh the name from which the modern one stems. When Ida captured Bamburgh in 547 Ad he kept the Celtic name Dynguoaroy but in the reign of Ethelfrith he renamed the settlement Bebbanburgh in honour of his wife Queen Bebba.

While Æthelfrith had been on the throne and the two kingdoms and been unified under one crown the young Edwin who had been dispossessed in 589 AD had the intervening years mustering support to reclaim his throne. In 616AD Edwin was ready to make his move and at the Battle of the River Idle he defeated and killed King Æthelfrith. Having taken the throne of Northumbria Edwin sought to secure his lineage and married the sister of the Christian king of Kent, Ethelburga in 625 AD. As part of the union Edwin embraced her religion and became the first Christian king of Northumbria. As part of his commitment to the faith, Edwin invited Paulinus, a colleague of Augustine, to convert his people at Bamburgh and across his kingdom. Edwin ruled until 633 AD when he was slain in battle by Penda, the King of the Mercia. Because Penda was a pagan, Edwin was regarded as a martyr and as a result was shortly after canonised as St Edwin.

When Edwin reclaimed his throne from Ethelfrith, the latter’s children retreated into exile to avoid the same fate as their father, One of the sons Oswald, was sent to Iona to be educated by the Irish monks there. When news of Edwin’s death reached them Oswald returned to Northumbria and was proclaimed king. His career was rather successful and in 634 AD he claimed a great victory against Cadwallon, King oof Gwynnedd. Then in 638 AD he expanded further north by capturing Dyn Eidin, now Edinburgh. By the end of his reign in 642 AD, the Venerable Bede tells us that he had successfully established himself as overlord of almost all of Britain. However, ruling from Bamburgh, Oswald met his end against a familiar foe, Penda of Mercia, and his body was dismembered. However, some Northumbrian soldiers were able to recover his arms and head and return them to Bamburgh. Regarded as another martyr his head was buried at Lindisfarne, and Bede reports that his arms were placed in a shrine made of silver within the Church of St Peter.

It is a coincidence that the arms survived as they are the focus of a legend which forms part of the case for Oswald’s sainthood. As the story goes, Oswald was informed of a band of beggars at the gate of Bamburgh’s keep. He lifted the silver dish from in front of him which was piled high with meat and gave it to them to eat. It is said that upon witnessing this act of charity Aidan, the Irish monk and founder of Lindisfarne Priory, prayed that the arm which did this should never decay. Perhaps then this was the reason for enshrining the fallen kings arms.

Good times, bad times

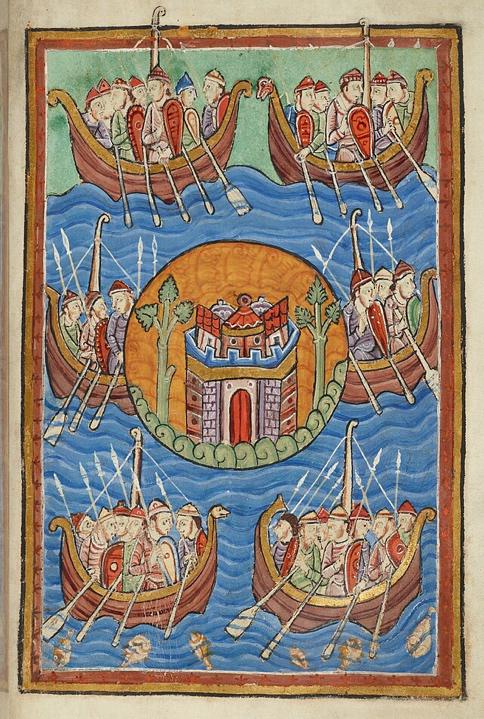

For two centuries after the deaths of Saints Edwin and Oswald the Kingdom of Northumbria continued in strong form, stretching for the Lothians of Scotland deep into the Midlands. Moreover, throughout that time Bamburgh remained at the centre of Northumbrian kingship and even when power shifted to York periodically, Bamburgh persisted as an important fortification from which to exercise authority. The good fortune was of course not to last and 793 AD marked the first incursion of the Vikings. This was a truly shocking event that caused great fear and panic among the Anglo-Saxons. After all the raid on Lindisfarne had happened a stone’s throw from Bamburgh Castle.

Over the proceeding decades the Viking presence in England became more significant. In the winter of 850 AD a Viking army camped at the mouth of the River Thames; in 865 AD another army landed in East Anglia and swept relentlessly into Mercia; by 866 AD York had fallen and in 867 AD the Vikings installed their first Norse king in Northumbria, Ecgberht I. Nevertheless, this did not spell the end completely for Bamburgh. Despite losing what was once the kingdom of Deira to the Vikings a family of High-Reeves were able to rule an Anglo-Saxon Northumbria which still consisted of lands between the River Forth and the Tees. In the end, this meant that Bamburgh survived as an Anglo-Saxon settlement right up until the Norman Conquest and preserved this beautiful coastal town’s place as a hugely important heritage site for the study of Anglo-Saxon Northumbria.

Written by C. James McPherson MA MSc.

Cover photo: GBC – June 2024