(A Map of the Kingdom of Northumbria circa 700 AD – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Map_of_the_Kingdom_of_Northumbria_around_700_AD.svg)

Northumbria was one of the most significant Anglo-Saxon kingdoms to the north of the Humber to ever exist. At its peak the Kingdom of Northumbria stretched from the Irish Sea to the North Sea with a northern border on the Firth of Forth and its southern border at the Humber.

As a military unit, Northumbria was strongest in the 7th century, when the authority of its kings, Edwin (616-632), Oswald (633-641) and Oswiu (641-670), was accepted by the southern kingdoms. It was in this period of domination that Northumbria gave its most significant contributions to Anglo-Saxon society. In terms of developments in medieval Christianity, the arts and works of intellect Northumbria experienced a period that could be described as a ‘golden age’.

Northumbria was made up of two originally separate kingdoms. Bernicia was based around the settlement at Bamburgh and the surrounding coast, while Deira was located further to the south. Ethelfrith, King of Bernicia (593-616), took control of Deira which in turn created the unified Northumbria. He was slain in battle by the forces of Edwin, a member of the Deiran Dynasty, who then ruled both regions as one. However, apart from this occasion and a few interruptions, the kingdom of Northumbria was always ruled by a member of the Bernician royal line. Although the kingdom of Mercia to the south managed on the whole to avoid Northumbrian expansion into their territory, the north was a different story entirely. At one point, the newly unified Northumbria was able to establish its rule as far north as the River Tay, in what is now modern-day Scotland.

The success of the kingdom of Northumbria was not to last, however. The cultural powerhouse and coherent political unit that was Northumbria was shattered by the incursions of the Vikings. The ‘Great Army’ of Danes took York in 866 and re-settled the area. Then in the first half of the 10th century more Scandinavians pushed inland from the Irish Sea and settled there also. Misfortune only multiplied when the kingdom of Scotland emerged and ousted the Northumbrians all the way back to the banks of the River Tweed. After that the Kingdom of Wessex exerted its authority over the whole of England and when the last Viking ruler of York was removed in 944, there ceased to be any kings of Northumbria. Instead, it was reduced to an earldom within the Kingdom of the English.

Despite its unfortunate end, the Kingdom of Northumbria produced many interesting sites of interest along the coastline. The most notable and those we will dive into a little deeper are Lindisfarne, Bamburgh, Yeavering, Hexham Abbey and Milfield.

Lindisfarne

Lindisfarne, a small island off the coast of Northumbria, has a rich and storied history that dates back to the 7th century. Lindisfarne was an important centre of Christianity and learning during this period, and it was here that St. Aidan, a Celtic monk from Ireland, arrived in 635 AD to establish a monastery.

The monastery on Lindisfarne became a major hub for the spread of Christianity throughout the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms. The monks on the island were known for their scholarly pursuits and their beautiful, illuminated manuscripts, which were highly prized throughout Europe. The monastery’s most famous manuscript, the Lindisfarne Gospels, is a masterpiece of Insular art and is considered one of the most important works of art from the Early Middle Ages.

In the 8th century, the Viking raids began to pose a significant threat to the monasteries of Northumbria, including Lindisfarne. In 793 AD, the Vikings attacked and destroyed the monastery on Lindisfarne, killing many of the monks and stealing their treasures. This event marked the beginning of the Viking Age in England and had a profound impact on the course of Anglo-Saxon history.

Despite this setback, the monastery on Lindisfarne was rebuilt, and it continued to be an important centre of learning and spirituality after the Norman Conquest of 1066. The island’s history is still celebrated today, with many visitors drawn to its picturesque landscape and ruined later medieval Priory.

Bamburgh

Bamburgh is a village north-east coast of Northumberland with a fascinating history as a location of great importance.

In the 6th century, Bamburgh was a strategic stronghold of the kingdom of Northumbria, with a timber fortification founded by Ida of Bernicia in 547. The village’s most prominent feature is Bamburgh Castle, which was built on top of the Anglo-Saxon fortifications but also earlier structures, likely a Roman signal station or a pre-Roman hillfort. The castle’s origins are unclear, but it is believed that the first timber castellum was constructed by King Æthelfrith of Northumbria (593-616) or his son, King Edwin (616-633).

Bamburgh was an important royal residence and military stronghold during the Anglo-Saxon period. It was said to have been the seat of King Æthelstan (924-939), who united the kingdoms of England and Northumbria under a single rule. The village was also a centre of learning and culture, with several Anglo-Saxon manuscripts and illuminated texts attributed to its monks.

During the Viking invasions of the 9th and 10th centuries, Bamburgh was repeatedly attacked and destroyed. The castle was abandoned in the 11th century, and the village was left in ruin. The Normans rebuilt the castle in the 12th century, but it remained a relatively insignificant settlement until the 19th century.

Today, Bamburgh Castle is a popular tourist attraction and a symbol of Northumberland’s rich cultural heritage. Archaeological excavations have uncovered numerous Anglo-Saxon artifacts and structures within the village, including the remains of a medieval church and a possible Anglo-Saxon cemetery.

Yeavering or Ad Gefrin

Ad Gefrin, a site nestled in the valley floor beneath the shadow of Yeavering Bell, holds a rich history that spans over 5,000 years with archaeological evidence dating back to the Bronze Age.

The site’s significance began to take shape in the 6th century when the Anglo-Saxon kings of Northumbria established a royal residence here. Unlike other kingdoms, Northumbria did not have a centralized seat of power, instead, the kings moved from one location to another, administering justice and collecting tribute from the local area. Ad Gefrin was one of these regional centers, where the royal court would reside for a period before moving on to other fortifications such as Bamburgh.

For over 100 years, Ad Gefrin played a significant role in Northumbrian history. In the 7th century, Bishop Paulinus preached to the King and Queen of Northumbria at their hall in Ad Gefrin, an event recorded by the Venerable Bede in his ‘History of the English Church and People’. Bede notes that Paulinus preached for 36 days and baptized his converts in the nearby River Glen.

Ad Gefrin was also home to some of Northumbria’s most renowned rulers, including Ethelfrith, Edwin, and Oswald, who was later canonized as St. Oswald. However, the site’s prosperity was short-lived, as it was attacked and destroyed by King Cadwallon of the Britons and King Penda of Mercia.

By the 8th century AD, Ad Gefrin had ceased to exist, and for over a thousand years, the site lay forgotten. It wasn’t until 1949 that aerial photography revealed the outlines of 6th-century buildings, allowing archaeologists to rediscover this important piece of Northumbrian history.

Hexham Abbey

The site which has been home to a church for over 1,300 years, dating back to Queen Etheldreda’s grant of lands to the Bishop of York, around AD 674, is a must see for its unique surviving architecture of the Anglo-Saxon period.

Hexham Abbey, a historic institution in the Kingdom of Northumbria, was founded in AD 674-8 by St. Wilfrid, a renowned figure in early English Christianity. The original Anglo-Saxon church, which occupied the space now occupied by the nave, still preserves its crypt and foundation of an apse.

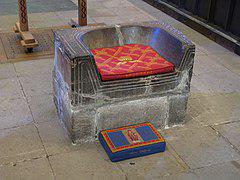

Furthermore, the Saxon crypt remains wholly intact and can be visited by the public. Hexham abbey also retains a 7th/8th century frith stool. In the medieval English, the concept of “frith” referred to a state of peace, security, and protection from harm. This notion was deeply ingrained in Anglo-Saxon culture, and it played a significant role in the tradition of seeking refuge in churches. When individuals sought asylum from conflict, persecution, or even the law, they would often flee to a place of worship, where they would find temporary safety and protection.

The frith stool, typically located near the high altar, served as a symbol of this sanctuary. It was believed to be a sacred and protected space within the church, where those seeking refuge could find solace and temporary reprieve from their troubles.

However, the peaceful existence of the abbey was disrupted by the Viking invasion of Tyneside in 875. Halfdan Ragnarsson, the Danish leader, ravaged the area and left Hexham Church in ruins. The once-thriving monastery was plundered and burnt to the ground, marking a significant turning point in its history and hence the survival of the sub-level crypt and little else of the Anglo-Saxon church.

With respect to the crypt, the influence of a Roman pilgrimage on Bishop Wilfrid’s architecture is evident in his decision to construct stone churches in Northumbria, inspired by the grandeur of Continental churches. However, the local craftsmen lacked the necessary expertise to work with stone, which presented a significant challenge.

Fortunately, a nearby Roman settlement at Corbridge offered an abundance of readily available building materials. It is likely that Wilfrid’s church was constructed primarily from stones salvaged from this site. As one descends into the crypt, the remnants of this Roman heritage become apparent, with intricate frieze patterns and decorative designs on the stones, evoking the grandeur of ancient Roman architecture.

Two inscribed stones in the crypt’s roof provide a glimpse into the church’s past, including a dedication to a granary and a fragment of an altar to Maponus Apollo, a blend of Celtic and Roman deities. As visitors take the steep stone steps down into the crypt, they are transported back to the early days of Christianity in England.

Milfield or Maelmin

Milfield, also known as Maelmin, is a significant archaeological site in Northumberland because it is where an Anglo-Saxon royal palace once stood. Located near the River Tweed, the site is believed to have been one of the primary residences of the kings of Northumbria after the destruction of Ad Gefrin.

The palace was built in the 7th century and was the centre of power and politics for the kingdom of Northumbria. It was here that the kings of Northumbria, including King Aldfrith and King Eadberht, resided and governed their kingdom. The site is notable for its well-preserved earthworks and remains of the Anglo-Saxon settlement, which are some of the most impressive examples of their kind in the county.

Archaeological excavations have revealed that the palace was a large and complex site, with multiple buildings and structures. The site includes a grand hall, known as the “great hall”, which was used for ceremonial and administrative purposes. Other buildings on the site include a church, a royal residence, and various workshops and storage facilities.

The site also provides evidence of the daily life and activities of the people who lived and worked there. Excavations have uncovered evidence of metalworking, weaving, and other crafts, as well as the remains of food and drink consumption.

In addition to its historical significance, Milfield is also an important cultural site. It is believed to be one of the few Anglo-Saxon royal palaces that has not been extensively modified or rebuilt over the centuries, making it an important window into the past. The site is now protected by English Heritage and is open to visitors who can explore the earthworks and learn about its rich history.

Written by C. James McPherson MA MSc.