The peaceful town of Fishguard can be found on the coast of Pembrokeshire, Wales. With a population of approximately 3,500, Fishguard as it appears today has two main areas: Lower Fishguard and the “Main Town’. Lower Fishguard is recorded as the site of the medieval hamlet from which the region has grown out of in the centuries since. It sits in a deep valley where the River Gwaun pours out into the sea, hence the towns Welsh name, Abergwaun, meaning ‘Mouth of the River Gwaun’. The main town consists of the parish church, the High Street and most of the modern housing developments that have cropped up since the 19th century. However, this unassuming and tranquil spot, which is home to many a fisherman, was not always so quiet. Fishguard is actually the site of the last invasion of British soil by a hostile military force …

The Battle of Fishguard was a military invasion of the United Kingdom by the forces of Revolutionary France during what became known as the War of the First Coalition. The short foray onto British soil, between the 22nd and 24th of February 1797, is as mentioned the most recent attempt by a foreign power to invade Britain.

General Lazare Hoche of the French military had planned a three-pronged attack on Britain in an effort to help the Irish Rebellion of the Society of United Irishmen. Hoche planned to land two forces of troops on mainland Britain to create a diversion for British forces while the third troop, the main body, would land in Ireland to prop up the rebellion. However, the most important factor in these kinds of endeavours and an issue which halted many an invasion over the centuries was of course weather. Adverse conditions prevented two of the forces from reaching their destination, but the third which planned to land in Wales and march on Bristol, went ahead.

The Invasion Force

The band of troops that made their way to Wales was made up of 1,400 soldiers from the La Legion Noire, a battalion consisting of several prisoners and conscripts under the command of Colonel William Tate, an Irish American. Tate had significant experience in the field, having fought against the British during the American War of Independence. In 1793, he received his first commission from the French to attack Spanish possessions in places like Florida and New Orleans. An issue with recruitment for those missions and his finances depleted he was forced to flee to Paris in 1795. Nevertheless, it was here that he met Lazare Hoche who recommended him for the planned invasion. His troops for the expedition were officially the Seconde Legion des Francs but were more commonly referred to as the Black Legion because they wore captured British Uniforms dyed a brown/black colour.

The naval phase of the invasion was led by Commodore Jean-Joseph Castagnier and was made up of four French warships, some of the newest constructed in the fleet. These were the frigates Vengeance and Resistance; the corvette Constance and a lugger christened the Vautour. Castagnier’s orders were to land Tate’s troops in Wales and then rendezvous with Hoche in Ireland to aid the main body of men.

Coming Ashore

The armed ensemble that came ashore near Fishguard numbered 1,400. Of that number around 600 were French Army regulars that had not received orders to join Napoleon Bonaparte in Italy, the remaining 800 were irregulars, mostly criminals, deserters and even British prisoners. Despite the rag-tag assortment, they were all heavily armed. As the men came ashore the fort at Fishguard fired a single blank cannon shot to alert the local volunteers that the enemy were coming. The exact landing point was at Carreg Gwastad Point on 22nd February under the cover of darkness. By the early hours of the morning on the 23rd the French had landed seventeen boatloads of soldiers, forty-seven barrels of gunpowder, fifty tons of cartridges and grenades as well as 2,000 containers of arms. The surd did however claim one of the rowing boats and several artillery pieces were lost to the waves.

The British Respond

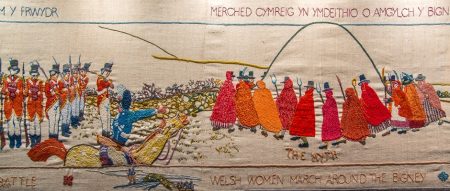

Once the French were ashore, disorder arose from within the ranks and many of the irregulars deserted the main battalion to loot nearby houses. The remaining men were left to face a hastily readied group of around 500 reservists, militiamen and sailors that were under the command of John Campbell, The Lord Cawdor.

Local landowner William Knox had raised the Fishguard & Newport Volunteer Infantry in 1794 in response to the House of Commons call to arms in the event of an invasion by the new Revolutionary Government of France. On the eve of the Battle of Fishguard the unit was the largest in Pembrokeshire and consisted of four companies totalling nearly 300 men. In command of the regiment was Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Knox, son of William Knox, a man who had purchased his commission and had seen no military action.

On the night in question, 22 February 1797, Thomas Knox received word of the invasion from a messenger boy and upon arriving at Fishguard fort he commanded the men of the Newport division to march seven miles to meet the French.

The Lord Cawdor, who was in command of the Castlemartin Troop of the Pembroke Yeomanry Cavalry, was some thirty miles from the invasion site but as soon as he received word, he mustered the Pembroke Volunteers and the Cardiganshire Militia and set off for Fishguard.

Naval support was provided by Captain Longcroft who assembled the press gangs and crews of two vessels stationed in Milford Haven, totally 150 seamen. He also had nine cannons brought to land, with six being sent to Haverfordwest Castle and three being made available for transport to Fishguard.

The Action

The French troops moved inland from their landing spot and secured some farmhouses for their own use. The impressive French grenadiers under a Lieutenant St. Leger had captured Trehowell Farm on the Llanwnda Peninsula which Colonel Tate used as his headquarters for the remainder of the mission. The French had orders to sustain themselves from the land, but the irregulars took this message as permission to loot and steal causing problems for the invasion force. The regulars however remained loyal to their officers and stood firm. As for the British at this time, Thomas Knox decided that he would attack the French head-on on the 23rd if he was not heavily outnumbered and so he sent out scouting parties to ascertain the strength of his foe.

As the morning light illuminated the land the French were located almost two miles inland occupying excellent defensive positions on the high grounds of Garnwnda and Carngelli. Despite the arrival of many Welsh locals armed with whatever they could find Knox was still short of men and was faced with a difficult choice. Should he: attack the French, defend Fishguard or retreat towards Haverfordwest where reinforcements were mustering in great numbers. He chose the latter and rendezvoused with Lord Cawdor and his men eight miles south of Fishguard.

Colonel Tate, in spite of his good geographical position, had lost most of his convict recruits who had drank themselves into oblivion or had deserted completely. Many of his officers came to him to encourage surrender, after all the naval support had now left for Ireland leaving them with no means of retreat.

On the afternoon of the 23rd Cawdor arrived at Fishguard with 600 men and three cannon. He ordered an attack whereby the men would march up a narrow lane towards the French encampment at Garngelli. However, Lieutenant St. leger and his band of grenadiers had snuck down from their position to a growth covered area to ambush the British. Cawdor, by wisdom or by sheer dumb luck called off the attack citing poor light and visibility.

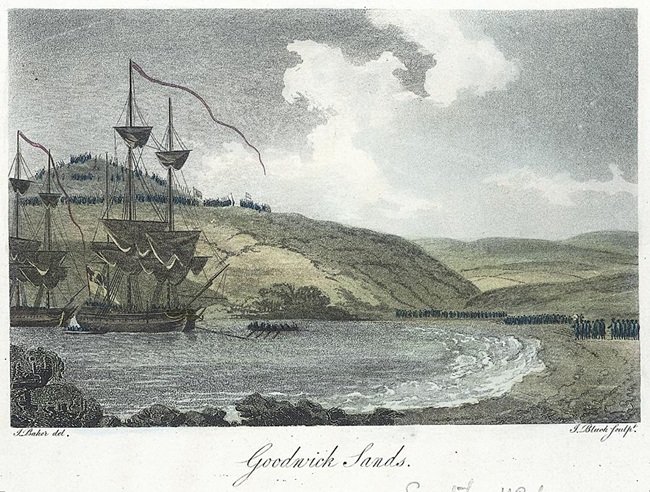

That evening, realising their position was too dire to resurrect, two French officers entered the Royal Oak where the British had set up headquarters to negotiate a surrender to Lord Cawdor. Cawdor told a little white lie and said that with his ‘superior force’ he would only accept an unconditional surrender, nothing more. He sent word to Colonel Tate that if he did not appear by 10am on the 24th at Goodwick Sands to surrender, the French would be attacked. That morning the British forces arrived at Goodwick Sands in battle formation and awaited the French response. Despite attempts to delay, Tate accepted the terms of unconditional surrender and the French marched down to the Sands and gave up their weapons, they were then marched to Haverfordwest Castle where they were to be initially imprisoned. Cawdor then rode out to Trehowell Farm to receive Tate’s official surrender, a document now lost.

After a short spell of imprisonment, Colonel Tate was allowed to return to France in 1798 as part of a prisoner exchange along with most of his La Legion Noire. One dares to think what might have been if the irregulars had not abandoned the invasion force or that all three battalions made it to their destinations, but as it turned out the Battle of Fishguard was nothing more than a short-lived, wine fuelled foray onto British soil. Nevertheless, Fishguard lives in infamy as the site of the last invasion of these British Isles.

Written by C. James McPherson MA MSc.