Sunderland Harbour

Sunderland Harbour

(Credit J. Thomas: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/deed.en)

Built up around both banks of the River Wear and with an extensive North Sea coastline we find the port city of Sunderland. The modern city is in fact the merging of three separate Anglo-Saxon era settlements: Monkwearmouth, on the northern bank of the river, and Bishopwearmouth and Sunderland to the south. In this period, St Peter’s Church was founded in Monkwearmouth and formed part of the famous Monkwearmouth-Jarrow Abbey which was a significant place of learning in early medieval England and home to ‘The Father of English History”, Bede. We also know that the Sunderland settlement was a vibrant fishing village and later a port which was granted a royal charter in 1179. Sunderland, as we will see, moved from strength-to-strength trading in coal and salt and by the fourteenth century it had become a hub of shipbuilding. The modern era had much in store for Sunderland too, the Industrial Revolution saw the area become famous for glassmaking and pottery and despite the decline of these industries in the late twentieth century, Sunderland became home to a large automotive industry and received city status in 1992. Overall, Sunderland has a rich and interesting history spanning over 1300 years, some of which we will cover here but so much more to be discovered if you take the trip yourself…

“Sundorlande” It’s origins and medieval past…

The first inhabitants of the Sunderland area that we know of were Stone Age hunter-gatherers and archaeological evidence of this has been uncovered in Monkwearmouth. During excavations around St Peter’s Church several examples of stone tools or microliths as they are known in the field were found, dated to between 4000 and 2000 BC. Also in this period, evidence suggests that Hastings Hill to the western end of Sunderland was an active Neolithic site and a place of ritualistic significance.

In pre-Roman Britain, it has been suggested that Sunderland was home to the Brigantes a tribe of ancient Britons. However, these peoples were subjugated by the Roman Empire who established a settlement on the southern bank of the River Wear. Several Roman artefacts have been recovered from the river itself, including stone anchors which might suggest that Sunderland was used as a port as far back as the 1st century AD.

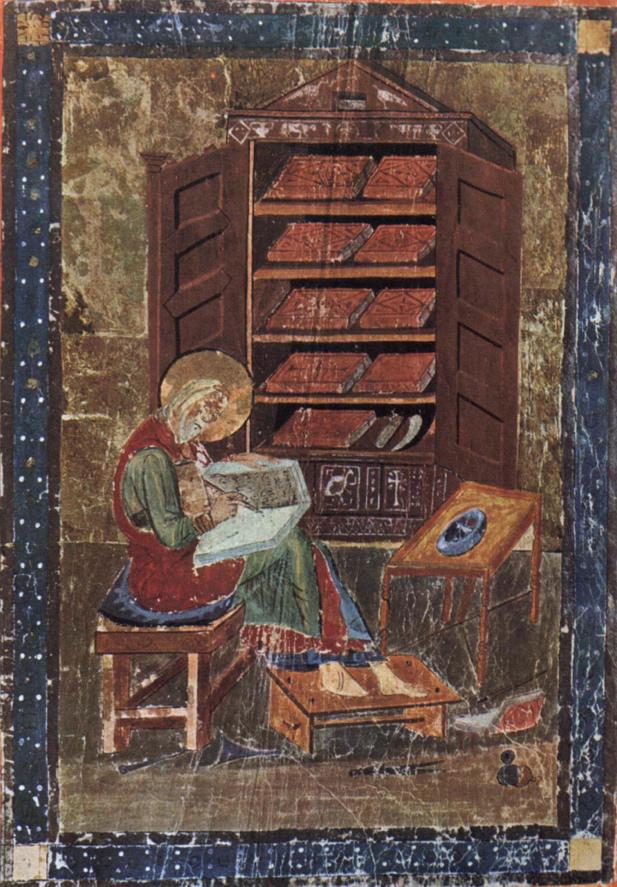

After the end of Roman Britain and the arrival of the Saxons, Sunderland became an important centre for the early Christian Church in England. Settlements at the mouth of the Wear can be dated to c. AD 674, when an Anglo-Saxon nobleman called Benedict Biscop was granted land by King Ecgfrith. Benedict founded a monastery (St Peter’s) on the northern bank of the river and the area became known as Monkwearmouth. Not only was Biscop’s monastery the first to be built in stone in Northumbria but he brought glaziers from France to work on the building, re-establishing glassmaking in England for the first time since the Roman era. After Benedict Biscop’s death a man named Ceolfrid became the new abbot of Wearmouth-Jarrow and elevated the church to become one of the major centres of learning in Anglo-Saxon England curating a library of approximately 300 volumes.

During the latter years of the 8th century Viking raids along the coast had threatened many of the Anglo-Saxon settlements and churches, by the 9th century

St Peter’s monastery had been abandoned. It was at this time that the land to the south of the Wear was granted to the Bishop of Durham, Wilgred, and became known as Bishopwearmouth.

By 1100, Bishopwearmouth was home to a fishing village located in what is now recognisable as Sunderland’s East End that went by the name of ‘sundorlande’ evolving later into Sunderland of course. It was this settlement that was granted a charter in 1179 that bestowed on its merchants the same rights as those enjoyed by their neighbours 10 miles north in Newcastle. Success was not instant however and it took Sunderland some years to mature as a port-town. Fishing remained the principal trade for much of the medieval period, herring in the 1200s, then salmon in 1300-1400s.

Sunderland in Black and White … the Salt and Coal Industry

The port of Sunderland eventually took off with thanks to the salt trade. Salt as an export can be found in the records from around the 13th century but it was in the 16th century that salt pans were laid at Bishopwearmouth Panns. The collected seawater was heated using coal and as the water evaporated the sodium chloride salt remained. The necessity for coal to sustain this industry prompted the creation of a coalmining community in and around Sunderland. The low-quality coal went to the salt industry and the premium coal was sold via the port, a further reason for its expansion. Salt and Coals were the primary exports from Sunderland right through to the 17th century. Coal especially boomed, with approx. 3,000 tons exported in 1600 rising to 180,000 tons by 1680.

The Rise of the Shipyards

From 1700 onwards the map of the River Wear could be described as dotted with shipyards for as long as the river was deep enough. In fact, after works were completed in 1717 to make the Wear River even deeper, shipbuilding in Sunderland grew at an exponential rate. Hundreds of wooden commercial vessels were constructed in Sunderland’s shipyards during this period and several warships were also commissioned by the Royal Navy. By 1750, Sunderland was regarded as the principal shipbuilding community in the country and by 1788 was Britain’s fourth largest port only topped by London, Liverpool and Newcastle. The industry only grew larger in the 19th century churning out 600 vessels across 31 different shipyards in 1815 alone. Furthermore, the records show a whopping 76 shipyards in 1840 with the number of constructed ships rising from the 600 in 1815 to over 3,000 vessels a year by 1850.

Sunderland and Sand

After coal and salt, Sunderland’s third largest export was glass. Modern glassworks opened in Sunderland during the 1690s and became an established part of the industrialised port. It’s evolution into one of the major trades was made possible by the good standard of sand coming into port from the Baltic Sea and other regions abroad as well as local access to limestone. By the mid-19th century glassmaking was at its peak. The Sunderland based company James Hartley & Co. was the number one glasswork in Britain and was the primary contractor in the construction of the Crystal Palace for the Great exhibition of 1851. In addition, there were at least 16 bottle works along the River Wear during the 1850s capable of making 70,000+ bottles a day to be exported across England and beyond.

Sunderland at War

When the First World War broke out in 1914 Britain’s industry shifted to a very large wartime output and Sunderland’s shipyards were required to expand the number of warships available to the Navy. As a result, Sunderland was the target of a Zeppelin air raid in 1916 which claimed the lives of 22 people and caused damage to industry and property. The Second World War generated similar circumstances, the shipyards which had declined in the inter-war years were once again teeming with life. But this once more meant the enemy targeted Sunderland, Luftwaffe bombing killed 267 people, destroyed or damaged over 4,000 homes and levelled several factories. Despite the actions of the Luftwaffe much of Sunderland’s built history survived the war, including St Peter’s Church, Monkwearmouth.

Towards the Future …

The latter half of the twentieth century began with a series of devastating blows to Sunderland’s industry. Shipbuilding ceased to exist by 1988, coalmining by 1993 and unemployment was at unprecedented levels. However, a glimmer of hope was offered by Nissan, the Japanese automotive manufacturer, who opened their UK headquarters in Sunderland in 1986. Since then, the Sunderland factory has become the largest car factory in Great Britain. Moreover, in 1992 Sunderland received city status and in the proceeding years much of the old shipyard land was redeveloped into a 21st century hub of housing, business and retail. Knowledge and learning also became a focus of the new Sunderland, somewhat reflective of its beginnings in the 7th century. The National Glass Centre was founded close to the site of St Peter’s Church dedicated to the history of glassmaking and the University of Sunderland invested in building a new campus and refurbishing its existing buildings. Thanks to these efforts, Sunderland has become an exciting modern coastal city still in touch with its long and proud history. So much so that in 2018 Sunderland was listed as the best place to live and work in the UK by a national survey.

Written by C. James McPherson MA MSc.