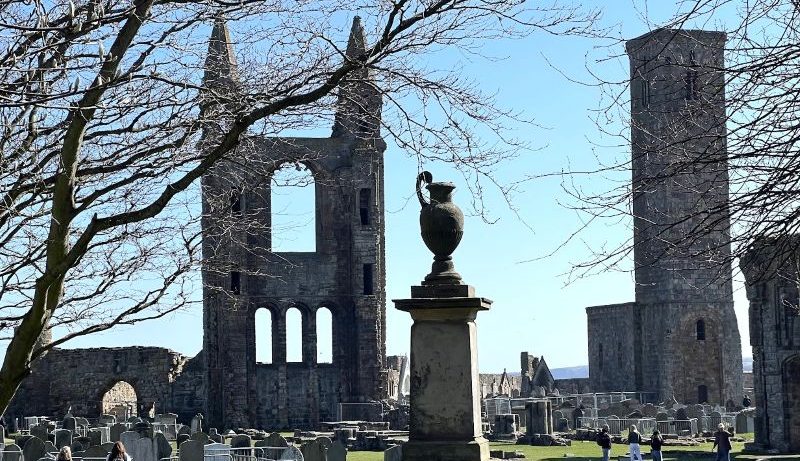

St Andrews Castle was one of the most significant medieval castles in Scotland. It was the home of the Archbishop of St Andrews, and adjacent to the cathedral which served as the ecclesiastical centre of the whole Scottish Kingdom. As such it was destroyed and rebuilt many times during the Wars of Independence as it changed hands between the English and Scots each vying for this important seat of authority. It once more became the focal point of conflict in the 16th century but this time between Protestants and Catholics and it is here, we find perhaps the most intriguing history of the castle.

At the outset of this period Archbishop James Beaton (1523-1529) maintained the castle in a state of great splendour and lavish hospitality. A visiting English ambassador even commented on this saying:

“I understand there hath not been such a house kept in Scotland many days before, as of late the said archbishop hath kept, and yet keepeth; insomuch as at the being with him of these lords, (Angus, Lennox, Argyle, etc), both horses and men, he gave livery nightly to twenty-one score horses.”i

Not closely the ambassadors surprise at how well the archbishop is able to host so many great men of the kingdom all at once. Alluding to the spaciousness of the Archbishop’s dining halls and accommodation. However, for his successor, comfort and joviality was not the primary concern.

James Beaton was succeeded by his own nephew, the lauded Cardinal David Beaton (1539-1546), a staunchly Catholic man. Fearful of the growing tensions between English Protestants and Scottish Catholics, Beaton neglected comfort in favour of defence. He had the castle altered so that it might withstand a heavy artillery attack, and he thought he might need it when he angered Henry VIII. Beaton refused to ratify the marriage contract put forward for his son Edward and the infant Mary, daughter of James V. Determined to unite England and Scotland if not by matrimony, then by force, Henry declared war in 1543.

While the Cardinal was going about his work to strengthen the fortification of the castle against impending attack in 1546, the garrison was easily, subtly, and successfully overcome by a small cohort of Protestant adherents who had entered the castle disguised amongst the masons who were employed on the consolidation works and thus were granted admittance to the castle and took possession before the suspicions of the soldiers were raised.

The invaders murdered Cardinal Beaton and hung his body from a wall-head, seemingly revenge for the burning of George Wishart for heresy some three months before.ii

The Protestants held out in St Andrews Castle, with the assistance of Henry VIII, for nearly a year. In that time, defending against some ingenious siege warfare with some ingenuity of their own …

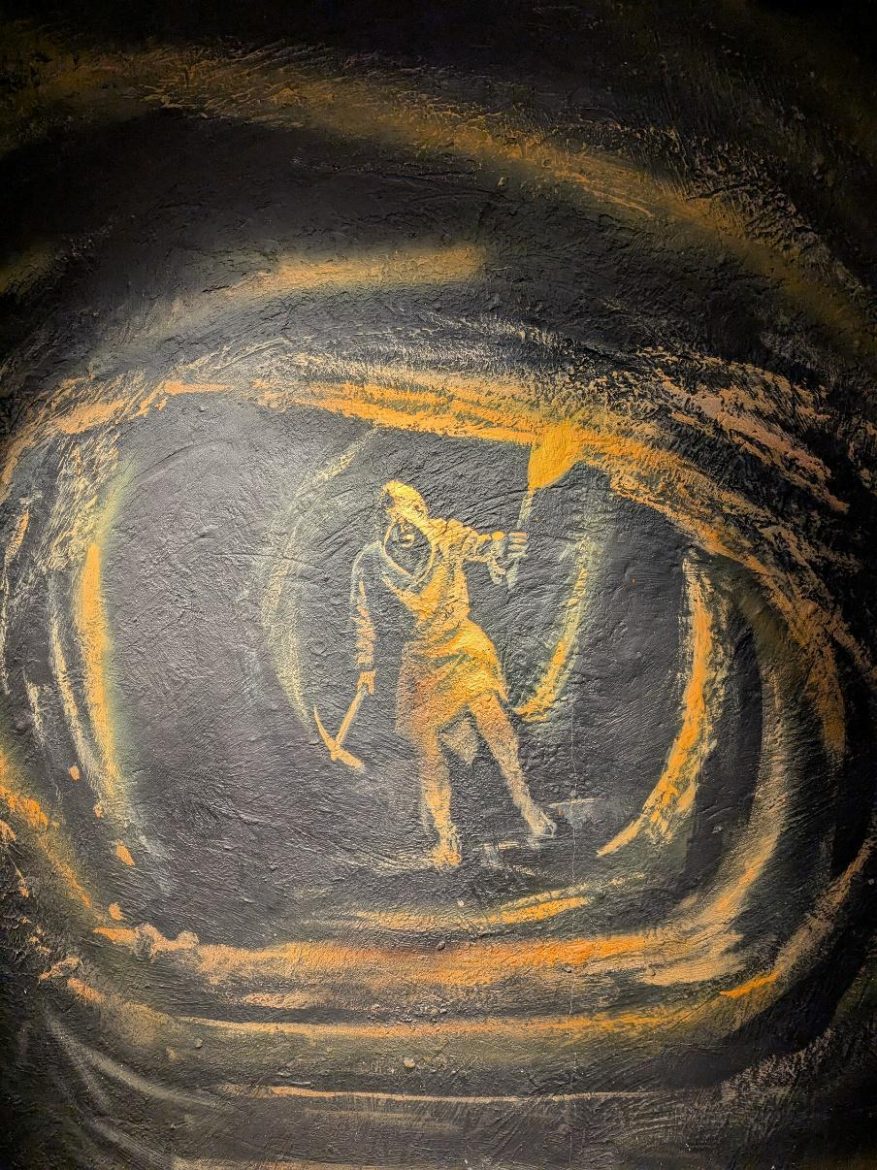

Surviving to this day is a very rare example of a medieval siege technique, a mine and counter-mine, tunnelled through solid rock, dating to the siege of 1546-47 ordered by James Hamilton, 2nd Earl of Arran, to retake the castle from the Protestants. In 1546 it was reported to the French ambassador in London that, “(James Hamilton) had mined almost to the foot of the tower by which he hoped to capture it, although the defenders were countermining and showed no great fear.”iii Despite the call of the Privy Council of Scotland to the King of France for help in the form of men skilled in the taking of fortifications, it appears the mines were undertaken prior to any French involvement by those English and Scots already on site.

The attackers began their tunnelling on the far side of the ditch to the south-east of the castle’s Fore Tower and dug a tunnel six feet wide and seven feet high with enough room to pass ponies through to remove rubble. With around twenty-seven feet to go to the base of the tower a Minehead was built from which branches could be built to undermine the castle’s foundations at multiple points.

The defenders of the castle were certain that a mine was being dug with the aim of bringing down the castle wall. Although it is not known exactly how they pinpointed where to dig, countermining was common in medieval siege warfare and a common technique used was to fill buckets with water and place them on the ground monitoring for vibrations from the pick axes below. Whichever method they employed there is evidence of a few early miscalculations in the form of two abandoned trial pits, one in each of the two chambers on opposing sides of the entranceway. Nevertheless, the attackers tunnel was abandoned at the Minehead as the defenders had driven their third mine from the east of the Fore Tower down to intercept them from a slightly higher level, albeit having turned eastwards for some feet before resuming their original course which proved to be the correct one. Hearing the attackers below and seeing the flicker of their candles through the small hole they had opened, the defenders descended into the Minehead and routed the enemy.

Today, visitors to the castle can descend into the mines via the countermine. It can be tricky to find but definitely should not be missed. Entered via the side of the dry moat you will find a few steep and rather uneven steps. At this point most people will be required to practically double over. If you are uncomfortable in confined spaces, I would recommend a haste retreat. Moving slowly through the incredibly cramped tunnel you will come to a fork in the shaft, one passage leads to a dead end, the other to another seemingly dead end. But looking down you will see a narrow opening with a metal ladder. Descending through the hole you find yourself in a much more open space. You have found the besieger’s mine. This section is high and broad eventually leading to a sealed entrance beneath a modern house on the corner of Castle Wynd. Finally, whilst in the mine look out for the pick-marks in the rocks that can clearly be seen in the floodlit areas and evidence of a coal seam which the tunnel happens to run through.

iCruden, Stewart. St Andrews Castle. (HMSO: Edinburgh, 1958)

iiLynch, Michael. Scotland: A New History. (PIMLICO: London, 2011)

iiiLetters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, vol. XXI, part ii, No. 380.

Written by C. James McPherson MA MSc.