Lindisfarne, also known as Holy Island, is a stunning tidal island situated just off the northeast coast of England and is a place of fascinating history. For the early medieval kingdom of Northumbria, Lindisfarne was the beating heart of the Anglo-Saxon Christian faith. What is more, the cult of St. Cuthbert drew pilgrims to the island and with-it wealth and donations of land. Something which would also make Lindisfarne a target for a particular group of marauders. But let’s not jump too far ahead …

The monks move in

Statue of St. Aidan outside the Medieval Priory Ruins – Photo: GBC June 2024

The history of Lindisfarne begins in 635 AD when the king of Northumbria, Oswald, invited an Irish Monk called Aidan to come over the water from Iona to take up the position of Northumbria’s bishop. In order to establish the bishopric, Oswald granted Aidan and his companions the small tidal island of Lindisfarne upon which they might build their monastery.

At this time Post-Roman England was fragmented and consisted of many smaller kingdoms ruled by Anglo-Saxon warlords. In the 7th century Oswald’s kingdom was by far the largest. The kingdom of Northumbria consisted of two main parts. One portion was called Deira which was centred on Roman York and the second was Bernicia which was located further to the north. In the reign of King Oswald (r.634-642 AD) power was focused on Bernicia from the royal palaces of Yeaverling, Maelmin and principally Bamburgh. Babmburgh being the key stronghold and port of authority only helped boost the fortunes of Lindisfarne Priory as it was located just six miles further up the coast. It has been suggested that the lasting success and growth of influence experienced by the monks of Lindisfarne can be attributed to the success of their missionary work, but most importantly the proximity to the royal dynasty in Bernicia must be noted.

The saintly Monk

Sometime in the 670s a monk by the name of Cuthbert joined the monastery on Lindisfarne. This particularly pious man would eventually rise to become their greatest ever monk-bishop and after his death, the primary saint in northern England during the Middle Ages.

As prior of Lindisfarne, Cuthbert reformed the monk’s way of life by conforming with the Rule of Rome rather than Rule of their founders in Ireland. This decision became a major point of contention and Cuthbert retied to an island, now known as St Cuthbert’s Isle, to live as a hermit. After some time there Cuthbert then moved even farther from the coast of Lindisfarne to the remote Inner Farne. However, his self-imposed exile did not last forever. In 685 AD King Ecfrith (r.670-685 AD) recalled Cuthbert to Lindisfarne to serve as its bishop. Although this thrusted Cuthbert into the world of kings and nobility, he became more well known as a pastoral carer, a seer and a healer. These saintly abilities set Cuthbert on the path to canonisation and his cause for sainthood was only strengthened after his death.

The cult of St. Cuthbert

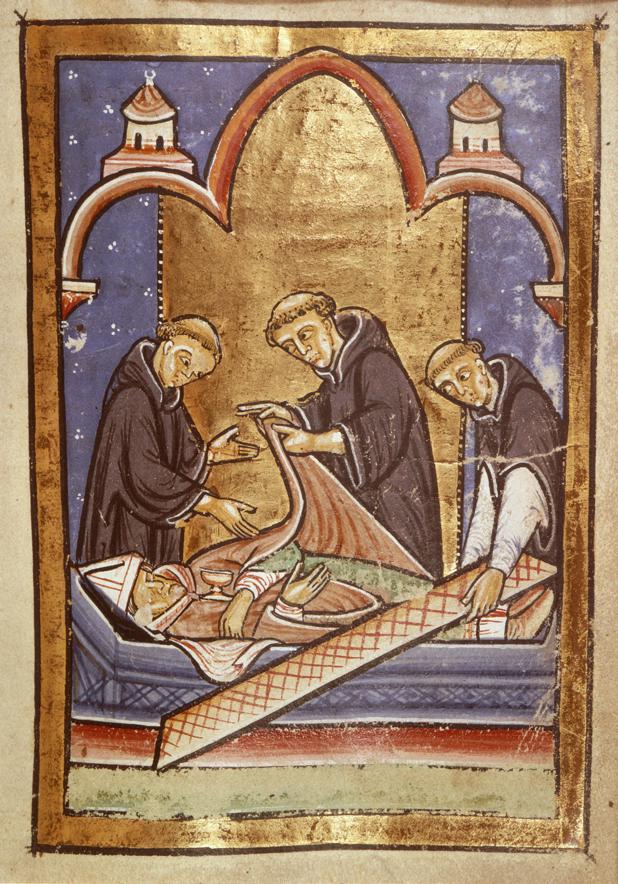

Monks discover the incorrupt body of Saint Cuthbert (British Library MS 39943 – Public domain)

Cuthbert died on 20 March 687 AD and was buried in a stone coffin within the central church on Lindisfarne. 11 years later the monks exhumed Cuthbert’s coffin and upon opening the stone lid discovered his body to be ‘incorrupt’, a sign of saintliness. After making this incredible discovery the monks of Lindisfarne placed the remains within a shrine coffin at ground level for veneration, thus marking the beginning of the cult of Saint Cuthbert.

Shortly after, reports of miracles attributed to Cuthbert began to crop up, quickly making Lindisfarne a place of major pilgrimage in Northumbria. With this popularity came great power and wealth. For almost century after Cuthbert’s passing the priory received grants of land from kings and nobles as well as gifts of money and precious objects from pilgrims wishing for the saint’s intervention.

This injection of people and capital meant that during this period Lindisfarne was able to consolidate itself as a place of learning. Between 710 AD and 725 AD the masterpiece of early medieval art that are the Lindisfarne Gospels were created.

Invaders from the North

On 8 June 793 AD Lindisfarne was attacked by Viking pirates, their first significant incursion into Western Europe. The reactions of contemporary writers were those of shock and horror, first that a violent unknown race of pagans could appear from the seas but secondly that Northumbria’s greatest saint had not intervened to protect his people. The famous scholar Alcuin of York, who was at the court of Charlemagne, wrote to King Æthelred and Bishop Higbald of Lindisfarne:

“Pagans have desecrated God’s sanctuary, shed the blood of saints around the altar, laid waste the house of our hope and trampled the bodies of saints like dung in the streets. … What assurances can the churches of Britain have, if St Cuthbert and so great a company of saints do not defend their own?”

For fear of this new Viking threat which grew throughout the 9th century and the desire to avoid a repeat of the harrowing events of the eighth of June the monks of Lindisfarne would eventually abandon the priory and set off through Northumbria carrying the relics and the wealth of their church.

A wandering church

As a result of growing Viking influence along the coastal areas of Northumbria the monks of Lindisfarne Priory began migrating to lands around Norham in the 830s, and in 875 AD took the hard decision to leave Lindisfarne for good.

After seven more years of wandering through northern England carrying the coffin of St. Cuthbert the monks chose to settle at Chester-le-Street where they built a church in the heart of the old Roman Fort. Although the monks had moved on it must be said that there was still a Christian community active at Lindisfarne throughout the Viking era. At least 23 carved stones dating from the 8th to the 10th century provide evidence that the Christian burial grounds were still in use. However, regardless of the strength of the community or the Anglo-Saxon army’s progress against the Norse at various stages in the proceeding century Cuthbert’s body would not return to the island and the island fell away in terms of its significance to the kingdom’s power and faith. In 995 AD the relics of St. Cuthbert moved once again but instead of returning home they were enshrined at Durham, where they remain today.

Written by C. James McPherson MA MSc.