The Wirral is a fascinating place which boasts stunning coastal views and is home to many quaint and beautiful village towns, but most importantly for this discussion the Wirral is teeming with evidence of its storied medieval past. In the early Middle Ages, the Wirral coastline was sought after, not for its beauty, but for its strategic importance. The Wirral peninsula’s 25 miles of coastline provides access to the Irish Sea in the North, the River Dee to the West and the River Mersey to East. The Wirral was an important incursion point for Irish and Norse invaders and as such was an important region to obtain and defend for the Anglo-Saxons in order to prevent Viking progress into the south of England.

Therefore, the region was pivotal to the battle for supremacy between Britons, Saxons and Vikings because the waterways were the main route for quick and efficient movement of fighting men in this period. Unsurprisingly then, the Wirral would become the battleground for one of, if not the most important, battle in English history in terms of the geography of the country we live in today.

The Arrival of the Saxons

(The arrival of the Angles, Saxons and Jutes, Miscellany of the Life of St.Edmund.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1130_Anglo-Saxon_Crossing.jpg )

When the Saxons arrived in England in the fifth century it was not long before they were battling with the native Britons for land and resources. After years of conflict and skirmish across England the Saxons did eventually gain the upper hand and in the early seventh century, they were ready to turn their attention to Chester. Chester acted as the city stronghold which controlled access to the Wirral peninsula and taking it under control would open the Wirral to Anglo-Saxon settlement.

The exact date of the capture of Chester by the Anglo-Saxon King Æthelfrith of Bernicia is unknown, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle gives a year of 605AD in one version and 606AD in another, but historian Charles Plummer believes a date of 615 AD or 616 AD fits our understanding of the history far better. Nevertheless, Æthelfrith and his Anglo-Saxon army defeated in battle a force of Britons from the Welsh kingdoms of Powys and Rhos to claim Chester for themselves. Lying at the southern land route into the Wirral this victory allowed for the settlement of many Anglo-Saxons and the creation of towns and villages all over the peninsula.

Traces of the Anglo-Saxons

The most obvious and lasting evidence of the Anglo-Saxon presence in the Wirral is what we can learn from place name evidence. Several towns and villages, particularly along the coast take their name from Old English words used in the early Middle Ages by their Anglo-Saxon inhabitants. One of the earliest settlements is Eastham whose name derives from its location: ham meaning home and it being to the east of a large inland Anglo-Saxon settlement of Willaston. Similarly, the villages of Great Sutton and Little Sutton also have a locative meaning derived from the Anglo-Saxon words for ‘south” and ‘Farm/Settlement’ again in relation to Willaston. Place names could also take the form of a personal name combined with a descriptive name. For example, the village of Bebington can be broken down into ‘Bebba’s Farm/Settlement’. Although we do not have an exact record of Bebba, he is likely to have been an Anglo-Saxon chief or principal landowner.

(St. Andrews Church, Bebington. E.J. Culley. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Standrewsbeb.jpg )

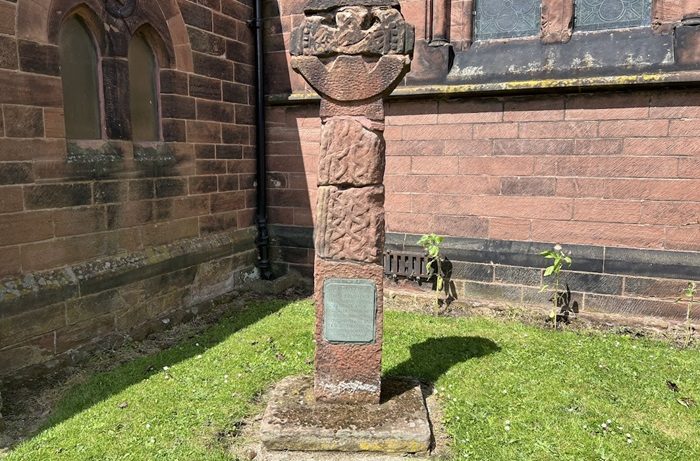

Physical evidence of the Anglo-Saxons in the Wirral has also been discovered, some of which only relatively recently. Archaeologists have discovered the foundations of an Anglo-Saxon church which once occupied the same site as St. Andrew’s Church, Bebington. Although the Anglo-Saxon structure was replaced by a Norman structure which itself has had modern renovations we can see evidence of the establishment of Christianity in the Wirral by the Anglo-Saxons. In the town of Bromborough, fragments of a 10th century Anglo-Saxon cross can be seen in the churchyard of St. Barnabas’. St. Barnabas Church was itself an Anglo-Saxon foundation probably built in the first half of the 10th century and may have been a monastery prior to the Norman conquest.

The cross, which is heavily reconstructed, can be found at the southside of the church porch and features a wheel-head cross. However, experts who have examined the St Barnabas Churchyard Cross have suggested that it is likely pieces of three separate stone carvings. Nonetheless, it is an interesting object to view on a trip to the lovely coastal town. Finally, in 2016 a team of archaeologists undertook a dig at Mark Rake, also in Bromborough. Here they uncovered a carved fragment, probably originating from sometime between 900 and 1100, featuring incised lines marking out a border with a cross in the centre. Again, signifying the presence of Anglo-Saxon Christianity in the Wirral. The fragment and other smaller finds were displayed by National Museums Liverpool as part of an exhibition and can be consulted on request.

The St. Barnabas Churchyard Cross, Bromborough. Photos: GBC (June 2024)

The Battle of Brunanburh 937 AD

Without a doubt, the most significant mention of the Wirral in Anglo-Saxon history is the suggestion of Bromborough as the site of the battle of Brunanburh. While the exact location of the battlefield is unknown, historians such as Michael Livingston and experts from Wirral Archaeology have concluded that extensive manuscript information and the discovery of battle artifacts pinpoint the Wirral as the most likely region in the country.

The battle of Brunanburh was fought in the Fall of 937AD. An Anglo-Saxon army led by Athelstan defeated and routed a force of Scots, Vikings, Picts and Welsh led by Anlaf Guthfrithsson the Hiberno-Norse Viking King of Dublin and the King of Alba (Scotland) Constantine II. This battle was so significant to our history because Athelstan was in command of what is regarded as the first unified army of the English. Athelstan had conquered the last Viking kingdom of York in 927AD which had made him the first Anglo-Saxon ruler of the whole of England. This victory against a combined force of all his northern enemies gave him a huge level of prestige and solidified the shape of what would become modern England.

The fighting at Brunanburh was fierce, with numerous casualties on both sides. Few contemporary accounts of the battle survive down to the present day, but a fantastic account is preserved within the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in the form of an epic poem. Some of the most poignant lines read:

“In this year (937) King Athelstan, lord of warriors, ring-giver of men, and also his brother, atheling Edmund, obtained eternal glory by fighting in battle with edges of swords around Brunanburh”.

“The enemies perished, the people of the Scots and sailors fell doomed. The field was darkened with the blood of warriors”.

“Never was there a greater slaughter of people killed on this island by the sword’s edge, even up until now or before this, of which the books of ancient scholars tell us; that is since from the east the Angles and Saxons arrived up over the broad seas to seek Britain, proud warriors, they overcame the Welsh, noble warriors, eager for glory, they conquered they country”.

And that is exactly what happened that day in the Wirral in 937 AD, ‘they conquered the country’. To quote Michael Livingston, ‘the men who fought and died on that field forged a political map of the future that remains, arguably making the Battle of Brunanburh one of the most significant battles in the long history not just of England, but of the whole of the British Isles’.

Written by C. James McPherson MA MSc.